Probiotics — Bacterial Strains Matter

There are literally billions of different strains of bacteria that can inhabit the human body. This fact alone makes a massive impact on choosing a probiotic supplement that can actually be effective. Understanding how these beneficial bacteria are classified may seem complicated at first (hopefully this article will simplify it!) but it’s critical to making an informed choice.

Unfortunately, many manufacturers count on the fact that many consumers don’t understand this information. Because it allows them to market probiotic supplements that are not nearly as beneficial as they could be.

How Bacteria Are Classified

Stick with us for a minute… we’ll get past the boring part as quickly as possible.

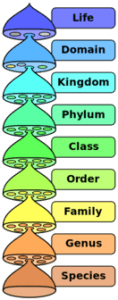

Going back to your High School science classes, all living things are classified into groups so they can be identified, named and studied. This is called Taxonomy. Life is divided into Domains, which are divided into Kingdoms, which are divided… etc. Here’s a chart of how Taxonomy currently breaks down all Life forms for handy reference:

Going back to your High School science classes, all living things are classified into groups so they can be identified, named and studied. This is called Taxonomy. Life is divided into Domains, which are divided into Kingdoms, which are divided… etc. Here’s a chart of how Taxonomy currently breaks down all Life forms for handy reference:

“Bacteria” is actually a Domain, the highest classification of living things.[1] So it’s not surprising that there are millions – perhaps even billions – of species of bacteria.

Fortunately, we don’t have to know about all of them. There are 5 relevant Genera (Genus groups) of bacteria that have been studied in relation to the human intestinal tract and probiotics.[2] Further, only certain Species out of those Genera have been studied. This narrows our focus quite a bit.

Probiotic Species Are Not Interchangeable

To put this in perspective, let’s look at how this works for people. There are various races of humans. For most of history those races were divided into countries. Within countries we had tribes. Within tribes we had villages. Within villages we had families. Within families we had households. Within households we had individual people.

Now, two children may be born into the same household. So they share all of the other classifications all the way back up to “human.” Let’s say one of the children – we’ll call him Bob -. grows up and the village discovers Bob is the best darn hunter the whole tribe has ever seen. Nobody’s gonna go hungry with Bob around.

Until the day Bob gets sick. Well, OK. Bob has a brother named Bill. They are nearly identical, grew up in the same house and all. Surely they’re practically interchangeable. So the village sends Bill out to hunt in Bob’s place. But Bill is not Bob, and he is really, really bad at hunting. The village isn’t getting any meat as long as they’re using Bill as their hunter.

Bill is good at other things, but he can’t hunt like Bob.

Strains of bacteria are just like Bill and Bob. Lactobacillus Acidophillus (Genus Lactobacillus, Species Acidophillus,) has been thoroughly studied.[3] Lactobacillus Curvatus does not have the same scientific backing.[4]

The bottom line is that not every strain of “good” bacteria makes for a good probiotic supplement. You have to make sure you’re getting strains in your supplement that have actually been studied, and actually found to benefit humans. Otherwise you might be sending a Bill out to hunt when you need a Bob.

Different Species Live In Different Places

Going back to our human example, a household lives in a particular place. As children, Bob and Bill lived in the same hut – you wouldn’t find Bob sleeping every night over at Tom’s hut because Tom’s parent’s aren’t his parent’s.

And here’s where this becomes relevant to your Probiotic supplement search: Each Genus populates a different area of the human intestinaltract.[5] Even more specifically, different species (sometimes called strains) of bacteria prefer to live in different areas of your digestive system.[6]

If a village wants to have huts in every area, it has to have enough households to cover that much space. If you want to cover your entire digestive system with beneficial bacteria, you want to get enough different strains to cover that much intestine.

So the next thing you want to think about when choosing a probiotic supplement is to look for one with strains from all 5 relevant Genera. Because you want to ensure that your entire system is covered, not just one small area.

The 5 Relevant Genera Of Probiotics

So as mentioned above, there are 5 Genera of probiotic bacteria that have been studied specifically for their effect on the human intestinal tract. Each of these 5 Genera “like” a different area of that digestive system. So finding a supplement with each of these is a good start.

These Genera are:

The Specific Strains You’re Looking For

This will not be an exhaustive list, and it will continue to be updated.

Specific strains of probiotics that have been studied and found to have benefits to humans include:

Lactobacillus

- L. Adidophilus is possibly one of the most studied strains in existence. It produces lactase,[12] the enzyme that breaks down the sugar in milk, and which is not naturally produced by those with lactose intolerance. It has been shown beneficial against diarrhea[13] , and combats pathogens in the digestive tract.[14] It also has been found to relieve symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome[15] and help increase immune responses.[16]

- L. Casei promotes recovery from diarrhea[17] , strengthens immunity[18] [19] , and may help deter the recurrence of certain types of bladder cancer.[20]

- L. Rhamnosus enhances immunity[21] , “significantly alters vaginal flora,”[22] (in other words, it was found to deter pathogens in the vagina which can lead to infections), and can help protect against urinary tract infections.[23]

- L. Brevis plays an important role in the synthesis of Vitamin D and Vitamin K.[24]

- L. Plantarum helps combat irritable bowel syndrome,[25] has antifungal properties,[26] and acts as a barrier in the gut to help prevent pathogens from being absorbed.[27]

- L. Salivarius has “antiinfective properties”[28] and can help cleanse the colon, combating diverticulitis pockets.[29]

Bifidobacterium

- B. Bifidum “significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome”[30] and boosts immune system response.[31]

- B. Lactis enhances the immune system[32] and can reduce the severity if E. Coli.[33]

- B. Longum can improve lactose digestion,[34] helps reduce inflammation in Ulcerative Colitis patients,[35] and alleviate some allergy symptoms.[36]

Lactococcus

- L. Lactis has shown promise in combating Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colitis.[37]

Streptococcus

Saccharomyces

- S. Boulardii may help with symptoms of Crohn’s disease[40] , ulcerative colitis[41] , or Inflammatory Bowel Disease.[42]

The Bottom Line

The bottom line when choosing a probiotic supplement is to choose one with multiple strains from multiple genera. Additionally, strains on the list above will ensure that the product you’re taking includes strains that have actually been studied and found to provide some benefit to humans.

For more information on choosing a Probiotic supplement, see our Probiotic Supplement Recommendations

See Also:

- Probiotics

- Probiotics – Bacterial Strains Matter

- Probiotics – How To Choose

- Probiotics Product Recommendations

- ^ Wikipedia contributors. “Bacterial taxonomy.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Sep. 2016. Web. 13 Sep. 2016.

- ^ Holzapfel, Wilhelm H., et al. “Taxonomy and important features of probiotic microorganisms in food and nutrition.” The American journal of clinical nutrition 73.2 (2001): 365s-373s.

- ^ Ljungh A, Wadström T (2006). “Lactic acid bacteria as probiotics”. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol. 7 (2): 73–89.PMID 16875422.

- ^ Wikipedia contributors. “Lactobacillus.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 Sep. 2016. Web. 13 Sep. 2016.

- ^ Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2013;53(6):641-58. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.553752. Probiotics and its functionally valuable products-a review. Kanmani P, Satish Kumar R, Yuvaraj N, Paari KA, Pattukumar V, Arul V. Source a Department of Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Pondicherry University, Pondicherry, 605014, India.

- ^ Br J Nutr. 2012 Aug;108(3):459-70. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511005824. Epub 2011 Nov 7. Comparative effects of six probiotic strains on immune function in vitro. Dong H, Rowland I, Yaqoob P. Source Department of Food and Nutritional Sciences, The University of Reading, Whiteknights, PO Box 226, Reading RG6 6AP, UK.

- ^ Klaenhammer, Todd R. “Functional activities of Lactobacillus probiotics: genetic mandate.” International Dairy Journal 8.5 (1998): 497-505.

- ^ Kailasapathy, Kaila, and James Chin. “Survival and therapeutic potential of probiotic organisms with reference to Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium spp.” Immunology and Cell Biology// 78.1 (2000): 80-88.

- ^ Kimoto, H., et al. “Lactococci as probiotic strains: adhesion to human enterocyte‐like Caco‐2 cells and tolerance to low pH and bile.”Letters in Applied Microbiology// 29.5 (1999): 313-316.

- ^ Wescombe, Philip A., et al. “Streptococcal bacteriocins and the case for Streptococcus salivarius as model oral probiotics.” Future Microbiology// 4.7 (2009): 819-835.

- ^ Czerucka, D., T. Piche, and P. Rampal. “Review article: yeast as probiotics–Saccharomyces boulardii.” Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics// 26.6 (2007): 767-778.

- ^ Kim, Hyung Soo, and Stanley E. Gilliland. “Lactobacillus acidophilus as a dietary adjunct for milk to aid lactose digestion in humans.” Journal of dairy science 66.5 (1983): 959-966.

- ^ Beck, Charles, and H. Necheles. “Beneficial effects of administration of Lactobacillus acidophilus in diarrheal and other intestinal disorders.” The American journal of gastroenterology 35 (1961): 522.

- ^ Gilliland, S. E., and M. L. Speck. “Antagonistic action of Lactobacillus acidophilus toward intestinal and foodborne pathogens in associative cultures.” Journal of Food Protection® 40.12 (1977): 820-823.

- ^ Sinn, Dong Hyun, et al. “Therapeutic effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus-SDC 2012, 2013 in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.” Digestive diseases and sciences 53.10 (2008): 2714-2718.

- ^ Gill, Harsharnjit S., et al. “Enhancement of natural and acquired immunity by Lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), Lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019).” British Journal of Nutrition 83.02 (2000): 167-176.

- ^ Isolauri, Erika, et al. “A human Lactobacillus strain (Lactobacillus casei sp strain GG) promotes recovery from acute diarrhea in children.” Pediatrics 88.1 (1991): 90-97.

- ^ Isolauri, Erika, et al. “Improved immunogenicity of oral D x RRV reassortant rotavirus vaccine by Lactobacillus casei GG.” Vaccine 13.3 (1995): 310-312.

- ^ Matsuzaki, T., et al. “The effect of oral feeding of Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota on immunoglobulin E production in mice.” Journal of Dairy Science 81.1 (1998): 48-53.

- ^ Aso, Yoshio, et al. “Preventive effect of a Lactobacillus casei preparation on the recurrence of superficial bladder cancer in a double-blind trial. The BLP Study Group.” European urology 27.2 (1994): 104-109.

- ^ Gill, Harsharnjit S., et al. “Enhancement of natural and acquired immunity by Lactobacillus rhamnosus (HN001), Lactobacillus acidophilus (HN017) and Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019).” British Journal of Nutrition 83.02 (2000): 167-176.

- ^ Reid, Gregor, et al. “Oral use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and L. fermentum RC-14 significantly alters vaginal flora: randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 64 healthy women.” FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 35.2 (2003): 131-134.

- ^ Barrons, Robert, and Dan Tassone. “Use of Lactobacillus probiotics for bacterial genitourinary infections in women: a review.” Clinical therapeutics 30.3 (2008): 453-468.

- ^ Council, Dairy. “Role of dietary lactobacilli in gastrointestinal microecology13.” The American journal of clinical nutrition 33 (1980): 2448-2457.

- ^ Niedzielin, Krzysztof, Hubert Kordecki, and Boz ena Birkenfeld. “A controlled, double-blind, randomized study on the efficacy of Lactobacillus plantarum 299V in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.” European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology 13.10 (2001): 1143-1147.

- ^ Ström, Katrin, et al. “Lactobacillus plantarum MiLAB 393 produces the antifungal cyclic dipeptides cyclo (L-Phe-L-Pro) and cyclo (L-Phe-trans-4-OH-L-Pro) and 3-phenyllactic acid.” Applied and environmental microbiology 68.9 (2002): 4322-4327.

- ^ Anderson, Rachel C., et al. “Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 2648 is a potential probiotic that enhances intestinal barrier function.” FEMS Microbiology Letters 309.2 (2010): 184-192.

- ^ Corr, Sinéad C., et al. “Bacteriocin production as a mechanism for the antiinfective activity of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104.18 (2007): 7617-7621.

- ^ Taylor, Kevin Douglas, and Simon Henry Magowan. “Methods And Kits For The Treatment Of Diverticular Conditions.” U.S. Patent Application No. 12/246,699.

- ^ Guglielmetti, Simone, et al. “Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life––a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study.” Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 33.10 (2011): 1123-1132.

- ^ Simone, C. De, et al. “Effect of Bifidobacterium bifidum and Lactobacillus acidophilus on gut mucosa and peripheral blood B lymphocytes.” Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology 14.1-2 (1992): 331-340.

- ^ Arunachalam, K., H. S. Gill, and R. K. Chandra. “Enhancement of natural immune function by dietary consumption of Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019).” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 54.3 (2000): 263-267.

- ^ Shu, Quan, and Harsharnjit S. Gill. “A dietary probiotic (Bifidobacterium lactis HN019) reduces the severity of Escherichia coli O157: H7 infection in mice.” Medical microbiology and immunology 189.3 (2001): 147-152.

- ^ Jiang, Tianan, Azlin Mustapha, and Dennis A. Savaiano. “Improvement of lactose digestion in humans by ingestion of unfermented milk containing Bifidobacterium longum.” Journal of Dairy Science 79.5 (1996): 750-757.

- ^ Furrie, Elizabeth, et al. “Synbiotic therapy (Bifidobacterium longum/Synergy 1) initiates resolution of inflammation in patients with active ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled pilot trial.” Gut 54.2 (2005): 242-249.

- ^ Xiao, Jin-zhong, et al. “Clinical efficacy of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum for the treatment of symptoms of Japanese cedar pollen allergy in subjects evaluated in an environmental exposure unit.” Allergology international 56.1 (2007): 67-75.

- ^ Steidler, Lothar, et al. “Treatment of murine colitis by Lactococcus lactis secreting interleukin-10.” Science 289.5483 (2000): 1352-1355.

- ^ Perdigon, G., et al. “Enhancement of immune response in mice fed with Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus acidophilus.” Journal of Dairy Science 70.5 (1987): 919-926.

- ^ Saavedra, Jose M., et al. “Feeding of Bifidobacterium bifidum and Streptococcus thermophilus to infants in hospital for prevention of diarrhoea and shedding of rotavirus.” The lancet 344.8929 (1994): 1046-1049.

- ^ Guslandi, Mario, et al. “Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease.” Digestive diseases and sciences 45.7 (2000): 1462-1464.

- ^ Guslandi, Mario, Patrizia Giollo, and Pier Alberto Testoni. “A pilot trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in ulcerative colitis.” European journal of gastroenterology & hepatology 15.6 (2003): 697-698.

- ^ Dalmasso, Guillaume, et al. “Saccharomyces boulardii inhibits inflammatory bowel disease by trapping T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes.” Gastroenterology 131.6 (2006): 1812-1825.